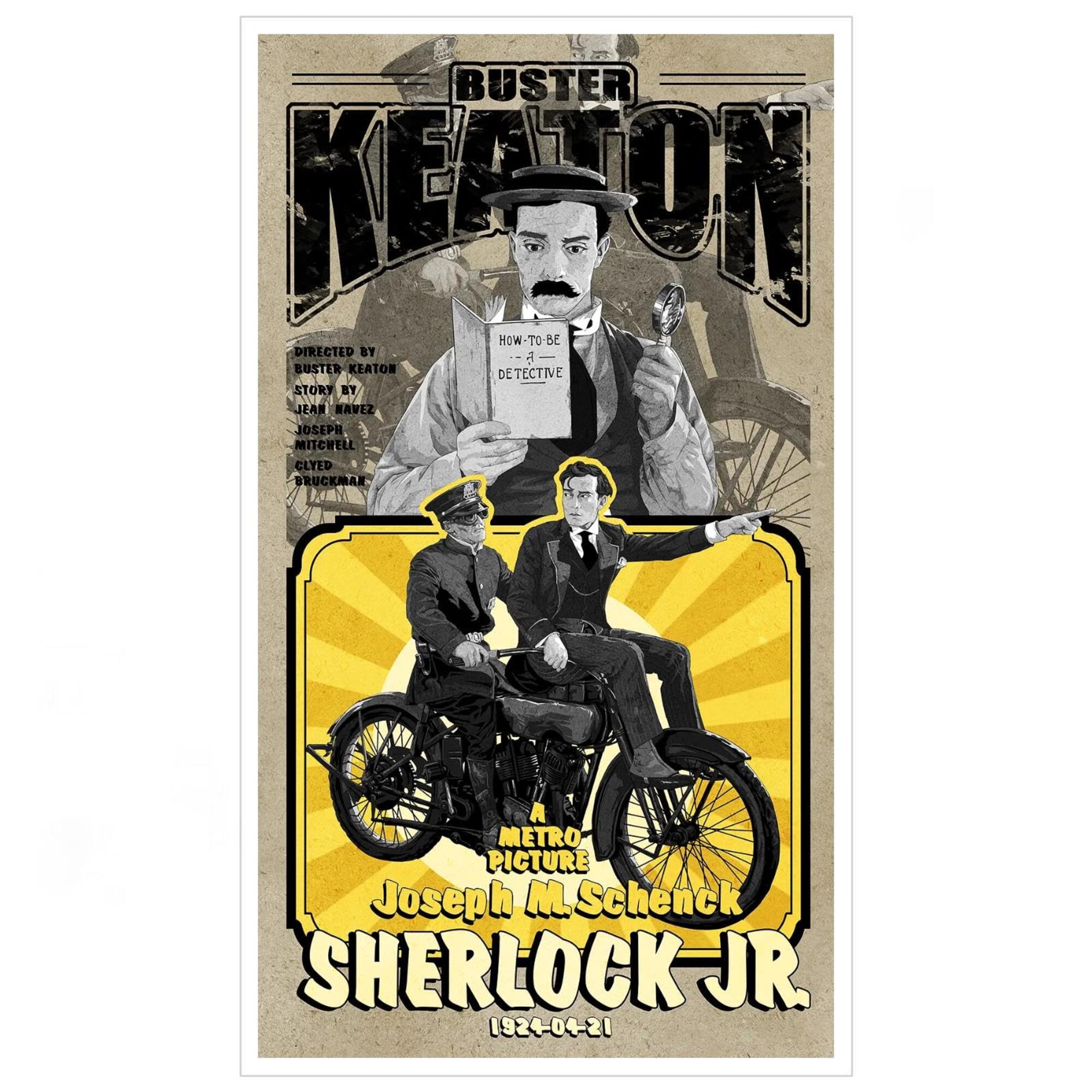

Sherlock Jr. (1924)

Sherlock Jr. (1924) is widely considered one of Buster Keaton’s finest achievements, a film that showcases his genius as both a physical comedian and a visionary director. A silent comedy with a touch of mystery, Sherlock Jr. is a testament to Keaton’s unmatched ability to blend inventive storytelling, complex stunts, and absurd humor. In just 45 minutes, Keaton delivers a film that is not only one of the best examples of silent cinema but also a groundbreaking work in the history of film.

In Sherlock Jr., Keaton stars as a mild-mannered movie projectionist who dreams of becoming a detective. When his fiancée (Kathryn McGuire) is deceived by a thief who steals a valuable watch, Keaton’s character steps into the role of Sherlock Holmes, using his imagination to solve the case. What follows is a series of inventive gags and jaw-dropping stunts, with Keaton using his exceptional physicality and visual storytelling to create one of the most technically impressive and hilarious films of the silent era.

Buster Keaton’s Genius: Physical Comedy and Visual Innovation

At the core of Sherlock Jr. is Buster Keaton’s incredible talent for physical comedy and his ability to create humor through innovative visual gags. The film is filled with iconic moments that showcase Keaton’s unmatched skills as a stunt performer, including scenes that require impeccable timing, daring physical feats, and extraordinary precision.

One of the most famous sequences involves Keaton’s character performing a series of near-impossible stunts, including a complex chase sequence involving a train and multiple costume changes. These stunts are all executed with Keaton’s signature deadpan expression, a key element of his comedic style. Keaton’s ability to perform these intricate stunts while maintaining his expressionless face is a hallmark of his style and a defining feature of his work in Sherlock Jr.

Keaton’s use of visual gags is also a standout in the film. The most remarkable example of this is the film’s surreal sequence in which Keaton enters a movie screen, transforming the world around him into a fantastical setting where he interacts with the fictional characters in the film. This groundbreaking use of the film-within-a-film technique was revolutionary at the time and showcased Keaton’s ability to experiment with cinematic form and create a visual language that was ahead of its time.

Story and Characters: A Humble Projectionist’s Dream

The plot of Sherlock Jr. is simple yet charming, focusing on the protagonist’s aspiration to become a detective while navigating the misunderstandings and comedic mishaps that arise from his ordinary life. Keaton’s character is a projectionist who, in his spare time, dreams of becoming a great detective like his cinematic idol, Sherlock Holmes. When his fiancée is fooled by a thief, Keaton’s character imagines himself as Sherlock Holmes and embarks on a mission to catch the criminal.

The film’s humor lies not just in the physical stunts but also in the absurdity of the situations Keaton’s character finds himself in. His character is a naive, yet determined figure who, despite his clumsiness and missteps, manages to solve the mystery in the most comedic and unlikely way possible. The contrast between his quiet, unassuming nature and the bold detective he imagines himself to be drives much of the humor, and Keaton’s performance in the role is both endearing and funny.

Innovative Use of Special Effects and Cinematic Techniques

Sherlock Jr. is also notable for its innovative use of special effects, which were groundbreaking for their time. One of the most impressive techniques in the film is the seamless use of double exposures and miniatures to create the illusion of Keaton interacting with the movie screen. In one scene, Keaton finds himself on a film set, where the laws of physics and reality bend in humorous ways. This sequence, which involved a combination of visual tricks and meticulously planned stunts, remains one of the most iconic moments in Keaton’s career.

Keaton’s use of visual effects is not limited to these surreal sequences. Throughout the film, he employed practical effects—such as clever camera angles and precise timing—to create the illusion of impossible stunts and situations. These techniques demonstrated Keaton’s forward-thinking approach to filmmaking, making Sherlock Jr. not only a comedic gem but also a film that pushed the boundaries of what was possible in cinema.

Legacy and Critical Acclaim

At the time of its release, Sherlock Jr. was not a major box office success, but its reputation grew significantly over the years. The film’s technical achievements, along with Keaton’s timeless comedic style, ensured that Sherlock Jr. would eventually be recognized as one of the greatest films of the silent era. In 1991, Sherlock Jr. was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress, honoring its cultural, historical, and aesthetic significance. In 2000, it was ranked #62 on the American Film Institute’s list of AFI’s 100 Years... 100 Laughs, solidifying its place in the pantheon of American cinema.

Critics have consistently praised Sherlock Jr. for its innovative use of visual effects, its impeccable comedic timing, and its charming lead performance by Keaton. The film’s influence on later filmmakers is immeasurable, with many citing Keaton’s work in Sherlock Jr. as a key inspiration in their own careers. David Thomson described it as "a breakthrough," highlighting its status as a key moment in Keaton’s career and in the history of film comedy.

Conclusion: A Timeless Masterpiece of Silent Comedy

Sherlock Jr. (1924) is one of the most brilliant achievements of Buster Keaton’s career and remains a defining work of silent cinema. The film’s innovative use of special effects, its incredible physical comedy, and Keaton’s remarkable performance ensure that it has stood the test of time as one of the finest examples of comedy ever made. Sherlock Jr. is a film that continues to entertain audiences and inspire filmmakers, proving that the art of silent film comedy is as relevant and exciting today as it was nearly a century ago.

For fans of silent cinema, slapstick comedy, or anyone interested in the genius of Buster Keaton, Sherlock Jr. is an essential viewing experience. It is a film that not only captures the spirit of its time but also continues to stand as a timeless example of cinematic innovation and comedic brilliance.

- 1924

- English

- 00h 45m

- 8.2 (IMDb)

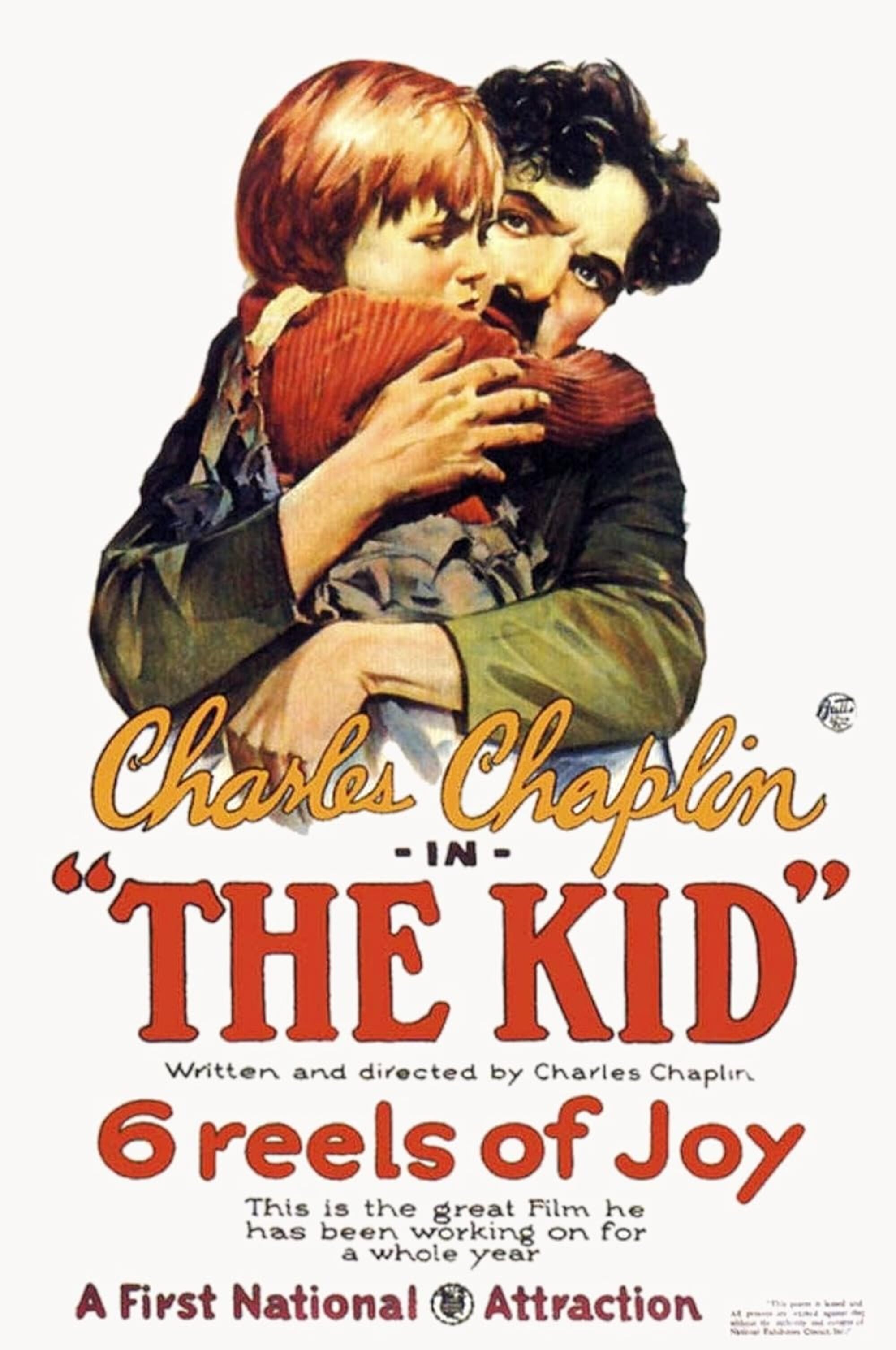

The Kid (1921)

The Kid (1921) is one of Charlie Chaplin’s most beloved and influential films, combining slapstick comedy with poignant emotional depth. Written, produced, directed by, and starring Chaplin, this film marks his first full-length feature as a director and remains one of the greatest works of the silent film era. Featuring a young Jackie Coogan in a breakout role as the titular "Kid," the film showcases Chaplin’s genius in blending humor with a tender story of love, loss, and resilience.

At the time of its release, The Kid was a huge commercial success, becoming the second-highest-grossing film of 1921. Over the years, its legacy has only grown, with the film being selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry in 2011 for its cultural, historical, and aesthetic significance. Today, The Kid is considered one of Chaplin’s finest films and a cornerstone of silent cinema.

A Heartwarming Story of an Unlikely Family

The plot of The Kid centers on the relationship between Chaplin’s iconic character, the Little Tramp, and a young boy whom he adopts. The film begins with an unwed mother who, overwhelmed and unable to care for her child, abandons him in a wealthy automobile with a note asking for love and care. However, the car is stolen by thieves, and the baby is left in an alley, where he is discovered by the Little Tramp.

At first, the Tramp tries to leave the baby with various passers-by, but when he reads the note, his heart softens, and he decides to take the child into his care. The Tramp names him John and adjusts his life, including his modest household, to provide for the child. Despite his poverty, the Tramp’s love for the boy is evident, and together they form a bond of mutual affection and dependence.

This unlikely, makeshift family becomes central to the film’s emotional core, with Chaplin’s character acting as both a loving father figure and a devoted caretaker. The film balances Chaplin’s trademark physical comedy with moments of real tenderness, showcasing his ability to elicit both laughter and sympathy from the audience.

Comedy and Social Commentary: The Struggles of the Tramp and the Kid

As the years pass, the Little Tramp and the Kid—now around five years old—live together in a cramped, humble room. They struggle to make ends meet, with the Tramp working as a glazier while the Kid helps him by breaking windows to allow the Tramp to repair them. The scenes of the Tramp and the Kid’s everyday misadventures are filled with slapstick humor, highlighting Chaplin’s impeccable timing and ability to create comedy out of ordinary situations.

However, as the story unfolds, Chaplin uses the Tramp’s relationship with the Kid to explore deeper themes, such as social class, abandonment, and the resilience of the human spirit. The film highlights the disparity between the Tramp’s love and devotion for the Kid and the lack of support they receive from society. The humor of the film often contrasts sharply with these more serious undertones, giving The Kid its unique blend of laughter and pathos.

The chance meeting between the Kid and his biological mother, now a successful actress, adds a layer of complexity to the plot. While the Mother (played by Edna Purviance) remains unaware of her child’s fate, she unknowingly crosses paths with him as she gives charity to poor children. This serendipitous encounter sets the stage for a dramatic reunion, as the story builds toward a heart-wrenching conclusion.

The Climax: A Fateful Separation and Reunion

In a pivotal moment in the film, the Kid falls ill, prompting the Tramp to seek medical help. However, when the doctor discovers that the Tramp is not the Kid’s biological father, he reports them to the authorities, and the Kid is taken away to an orphanage. The Tramp’s desperate pursuit to keep his makeshift family intact leads to a series of chaotic yet poignant events, culminating in a heart-stopping scene in which the Tramp is separated from the Kid, only to search for him frantically through the streets.

The emotional stakes reach a fever pitch when the Tramp, heartbroken and desperate, is eventually reunited with the Kid and his mother in a tender moment of reconciliation. The film’s climax, where the Tramp is welcomed into the Mother’s home, offers a satisfying and deeply emotional resolution, reinforcing the central theme of love overcoming adversity.

Chaplin’s Directorial Brilliance and Jackie Coogan’s Performance

As both director and lead actor, Chaplin’s vision for The Kid is remarkable in its seamless blending of slapstick and emotional depth. The film is a showcase for Chaplin’s ingenuity as a director, with every gag and stunt executed with precision and timing. The Little Tramp’s famous antics—such as the sequence in which he tries to feed the Kid using his own hat—demonstrate Chaplin’s comedic genius, while the quieter moments, in which the Tramp cares for the Kid, highlight his ability to convey deep emotion without words.

The film also marks Jackie Coogan’s first major screen role, and his performance as the Kid is nothing short of extraordinary. Coogan, despite being very young at the time, holds his own against Chaplin, perfectly capturing the innocence, curiosity, and vulnerability of his character. The emotional chemistry between Chaplin and Coogan is palpable, and their bond forms the heart of the film.

Legacy and Lasting Impact

The Kid is not only one of Chaplin’s most personal works but also a film that has had a lasting impact on cinema. Its innovative mix of comedy and drama, its heartfelt performances, and its exploration of universal themes have ensured its place in film history. In 2011, The Kid was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress, cementing its legacy as one of the most culturally significant films of all time.

The film’s influence can still be seen in modern filmmaking, with Chaplin’s blend of humor and pathos paving the way for later filmmakers who sought to capture both the absurdity and the humanity of life. Its impact on the silent film era and on the broader history of cinema remains immeasurable.

Conclusion: A Timeless Classic of Silent Cinema

The Kid (1921) is a true masterpiece of silent cinema, blending Chaplin’s unique comedic brilliance with a touching and emotionally resonant story. The film’s timeless appeal lies in its universal themes of love, loss, and the human capacity for resilience, making it one of the greatest films of the silent era.

For anyone interested in the history of cinema, Chaplin’s The Kid is an essential viewing experience. It remains an enduring testament to Chaplin’s genius, both as a filmmaker and as a performer, and continues to capture the hearts of audiences around the world, nearly a century after its release.

- 1921

- English

- 01h 08m

- 8.2 (IMDb)

Nosferatu (1922)

Nosferatu: A Symphony of Horror (1922) is one of the most influential and groundbreaking films in the history of cinema. Directed by F.W. Murnau, this silent German Expressionist horror film introduced audiences to the iconic character of Count Orlok, a monstrous vampire who preys on the innocent. Loosely based on Bram Stoker’s 1897 novel Dracula, Nosferatu is a pioneering work that helped shape the horror genre and set the stage for countless vampire films that followed.

Despite its unauthorized adaptation of Dracula, Nosferatu has survived as one of the most celebrated films of the silent era. Its innovative cinematography, eerie atmosphere, and haunting performances, particularly by Max Schreck as Count Orlok, have cemented its place in film history. Today, Nosferatu is widely regarded as a masterpiece, influencing both the horror genre and the development of cinema as a whole.

The Story: A Tale of Vampirism and Plague

Nosferatu follows the story of a young estate agent, Hutter (played by Gustav von Wangenheim), who is sent to the remote Carpathian Mountains to conduct business with a reclusive nobleman, Count Orlok. Upon arriving at Orlok’s castle, Hutter discovers that his new employer is a vampire who plans to move to the nearby town, bringing with him death and disease.

As Orlok begins his journey to the town, Hutter’s wife, Ellen (Greta Schröder), becomes increasingly aware of Orlok’s sinister intentions. She soon learns that she is the vampire’s intended victim, and the only way to stop Orlok is for her to sacrifice herself. The film builds to its dramatic and terrifying climax, where the vampire’s deadly influence brings a plague to the town, and only Ellen’s ultimate act of bravery can end Orlok’s reign of terror.

While the film’s plot closely mirrors that of Stoker’s Dracula, the names and certain elements of the story were altered to avoid copyright infringement, with Count Dracula being renamed Count Orlok. Despite these changes, the film clearly draws from the novel’s central themes of fear, seduction, and the battle between good and evil. Nosferatu takes a more immediate and personal approach by setting the story in a German context, making it more relatable to contemporary German-speaking audiences.

Max Schreck’s Iconic Performance as Count Orlok

One of the most memorable aspects of Nosferatu is Max Schreck’s portrayal of Count Orlok. Schreck’s performance is legendary for its unsettling, grotesque qualities. Orlok is depicted as a shadowy, nightmarish figure with exaggerated features—his long fingers, sharp teeth, and hunched posture create an image of terror that is unlike any other vampire seen before or since. Schreck’s physicality and his eerie presence contribute to the film’s deeply unsettling atmosphere.

Schreck’s portrayal of Orlok has since become a defining image of horror in cinema. The character’s appearance, particularly his insect-like movements, set a template for the monstrous vampire figure in subsequent films, distinguishing Orlok from the more charismatic and seductive vampires that would later become popular in the genre.

German Expressionism: Cinematic Innovation and Atmosphere

Nosferatu is a prime example of German Expressionist cinema, a movement that sought to depict subjective emotions and distorted realities. The film’s visual style is characterized by exaggerated sets, sharp lighting contrasts, and eerie shadows—all of which contribute to the film’s unsettling atmosphere. The distorted and jagged architecture, particularly in scenes set in Orlok’s castle, adds to the sense of disorientation and dread, reflecting the inner turmoil and fear of the characters.

Murnau’s use of light and shadow is also a defining feature of the film. The eerie play of light, especially in scenes involving Orlok, heightens the supernatural and nightmarish qualities of the vampire. The use of shadows, combined with Schreck’s physical performance, creates an atmosphere of dread that permeates the entire film. These stylistic choices were revolutionary for the time and became a hallmark of the horror genre.

The film also employs innovative camera techniques, such as slow zooms and carefully choreographed shots, to build tension and convey the growing danger of Orlok’s presence. Murnau’s attention to detail in both the cinematography and the use of space helps to create a sense of claustrophobia and impending doom.

Legal Disputes and Survival

Nosferatu was initially released without permission from Bram Stoker’s estate, and the film’s creators faced a lawsuit for copyright infringement. As a result, the court ordered that all copies of the film be destroyed. However, several prints of the film survived, often through accidental preservation, and Nosferatu was rediscovered in the 1920s and 1930s. Over time, the film’s significance became increasingly recognized, and it became a cornerstone of the horror genre.

The legal issues surrounding Nosferatu have since become part of its fascinating history. The film’s unauthorized nature and its subsequent survival give it a sense of rebellion and resilience, adding to its mystique and cultural value.

Legacy and Cultural Impact

Nosferatu has endured as one of the most influential films in the horror genre. Its portrayal of the vampire as a monstrous, otherworldly creature helped to redefine the archetype for future generations. The film’s haunting imagery, particularly Orlok’s terrifying appearance, continues to be a defining image of horror in popular culture.

Critics and historians have long recognized Nosferatu as a film that set the template for the modern horror genre. Its atmosphere, pacing, and use of visual effects influenced countless filmmakers, including those working in both the horror and fantasy genres. The film’s lasting impact can be seen in later vampire films, such as Nosferatu the Vampyre (1979) by Werner Herzog, which pays homage to the original while updating its themes and visual style.

In 1999, Nosferatu was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress for its cultural, historical, and aesthetic significance. Its influence on cinema is immeasurable, and it continues to be regarded as one of the greatest films ever made.

Conclusion: A Masterpiece of Horror Cinema

Nosferatu: A Symphony of Horror (1922) is not just a pivotal film in the history of the horror genre; it is a cinematic masterpiece that continues to captivate audiences more than a century after its release. F.W. Murnau’s innovative direction, Max Schreck’s haunting performance as Count Orlok, and the film’s expressionist visual style have cemented Nosferatu as one of the most important films in the history of cinema.

For anyone interested in the origins of horror cinema, Nosferatu is an essential film. Its dark, eerie atmosphere, groundbreaking visuals, and lasting cultural impact ensure that it remains a timeless classic in the genre.

- 1922

- German

- 01h 28m

- 7.9 (IMDb)

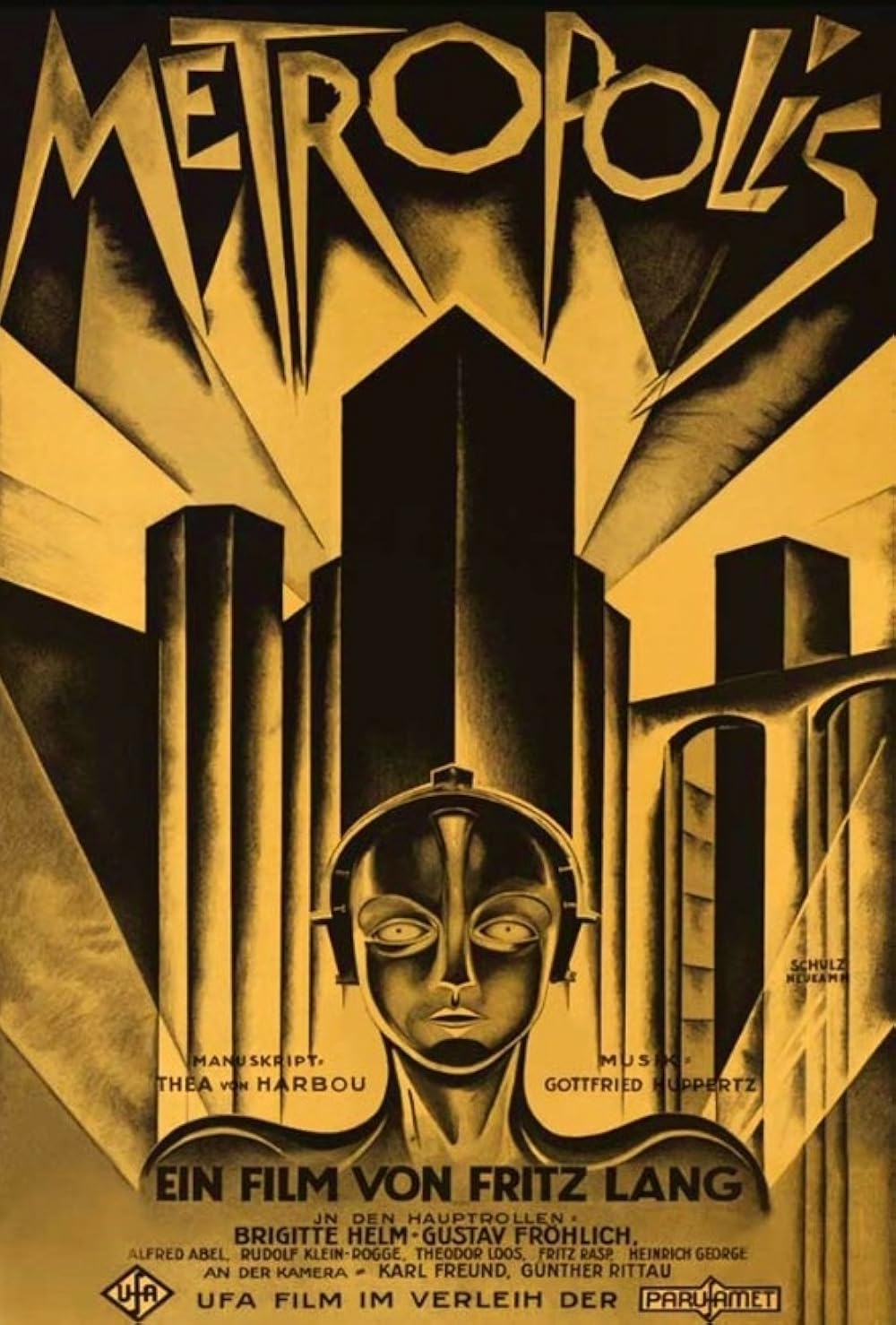

Metropolis (1927)

Metropolis (1927), directed by Fritz Lang, is a monumental work in the history of cinema and one of the pioneering science fiction films of the silent era. Based on Thea von Harbou’s 1925 novel of the same name, the film presents a dystopian vision of the future set in a vast, technologically advanced city. With its stunning visual effects, elaborate sets, and ambitious themes, Metropolis has become an enduring symbol of cinematic innovation, influencing generations of filmmakers and shaping the sci-fi genre for decades to come.

Produced during Germany's Weimar Republic and filmed over 17 months, Metropolis was one of the most expensive films of its time, with a budget exceeding five million Reichsmarks. Despite initial mixed reactions from critics, Metropolis’s visionary direction, art design, and special effects have ensured its place as one of the greatest films ever made.

A Dystopian Vision: Class Conflict and the Search for Unity

At its core, Metropolis tells the story of the division between the wealthy elite and the oppressed working class in a futuristic city. The film follows Freder (Gustav Fröhlich), the privileged son of Joh Fredersen (Alfred Abel), the city’s master, who becomes aware of the harsh conditions endured by the workers who run the city's vast machines. Freder’s awakening to the suffering of the workers and his eventual involvement with Maria (Brigitte Helm), a saintly figure to the workers, forms the emotional heart of the story.

The film’s central message is encapsulated in its final inter-title: “The Mediator Between the Head and the Hands Must Be the Heart.” This phrase speaks to the film’s critique of the social and economic divide between the powerful elite (the "head") and the laboring masses (the "hands"), calling for empathy and understanding as a means to bridge the gap and achieve unity. The film's exploration of class struggle, industrialization, and the dehumanizing effects of technology still resonates with modern audiences, making it a timeless commentary on social inequality.

Innovative Visual Style and Special Effects

Metropolis is renowned for its groundbreaking visual effects and art direction. The film’s sets and design, led by Otto Hunte, Erich Kettelhut, and Karl Vollbrecht, draw influences from opera, Bauhaus, Cubist, and Futurist movements, incorporating elements of Gothic architecture and surreal landscapes. These visually stunning and sometimes disturbing sets, such as the towering cityscape, the workers' subterranean catacombs, and the towering, mechanical machines, create a striking contrast between the opulence of the ruling class and the squalor of the workers.

The film’s use of special effects was revolutionary for its time. One of the most iconic images from Metropolis is the transformation of Maria into the robot double (played by Brigitte Helm), which is considered one of the first uses of an actor’s likeness being turned into a robot or automaton. Lang’s use of miniatures, superimposition, and expressive lighting techniques also helped to create a sense of scale and grandeur that was unprecedented in silent cinema.

Lang’s direction, combined with his collaboration with his creative team, resulted in a visually striking and thematically rich film that pushed the boundaries of what was possible in film at the time. The sophisticated special effects and expansive sets in Metropolis became an inspiration for later films, particularly in the genres of science fiction and film noir.

Themes of Authority, Technology, and the Human Spirit

Metropolis is a profound exploration of the dangers of unchecked technological advancement and the potential for human exploitation within an industrialized society. The film critiques the alienation of workers who are dehumanized by the machines they operate and the authoritarian control exerted by Joh Fredersen over both the city and its people.

At the same time, Metropolis explores the tension between human emotion and the cold, mechanized world. The characters of Maria and Freder represent the idealism and hope for change, while the film’s antagonist, the mad scientist Rotwang (Rudolf Klein-Rogge), embodies the destructive potential of technological ambition when combined with personal obsession.

The character of Maria, both a saintly figure and the robot double, represents the duality of human nature—innocence and corruption. The robotic version of Maria, who is used as a tool of manipulation, serves as a metaphor for how technology can be twisted for power, while the real Maria’s unwavering faith in humanity offers a vision of hope for a better future. The film ends on a hopeful note, suggesting that cooperation between different classes (the head, the hands, and the heart) is essential for societal progress.

Mixed Reception, but Enduring Legacy

Upon its release, Metropolis received a mixed critical reception. Critics praised the film’s visual beauty and its complex special effects, but they also criticized the story as overly simplistic and its political message as naive. H.G. Wells, for instance, dismissed the film as "silly," while other critics were put off by its alleged communist undertones. The film’s long running time and initial version, which was cut substantially after its German premiere, also contributed to mixed reactions.

Despite the early mixed reception, Metropolis has since been recognized as one of the most important and influential films ever made. Its visionary direction, pioneering special effects, and profound social commentary have made it a touchstone in the history of cinema. The film has inspired generations of filmmakers, particularly in the genres of science fiction and film noir, and remains a key reference in discussions of cinematic innovation.

Restoration and Preservation

The film underwent several restoration attempts over the years, with the most significant being in 2001 when a nearly complete version of Metropolis was shown at the Berlin Film Festival. In 2008, a damaged print of the original cut was discovered in an Argentine museum, and after extensive restoration, Metropolis was 95% restored. The newly reconstructed version was released in 2010, ensuring that Lang’s vision could be appreciated by contemporary audiences.

In 2001, Metropolis was added to UNESCO's Memory of the World Register, making it the first film to be thus distinguished. Its preservation and continued influence on modern filmmaking solidify its status as a landmark in the history of cinema.

Conclusion: A Timeless Sci-Fi Masterpiece

Metropolis (1927) is more than just a pioneering science fiction film; it is a cinematic work of art that continues to inspire filmmakers and captivate audiences nearly a century after its release. Fritz Lang’s visionary direction, combined with the film's groundbreaking visual effects and its timely social critique, ensures that Metropolis remains one of the greatest films ever made. The themes of class struggle, the dangers of industrialization, and the potential for human redemption resonate just as strongly today as they did in the 1920s.

For fans of cinema, science fiction, and the history of film, Metropolis is an essential experience. Its lasting legacy, profound impact on the genre, and remarkable visual storytelling guarantee its place in the pantheon of cinematic masterpieces.

- 1927

- German

- 02h 33m

- 8.3 (IMDb)

_698d9b69556ba.png)

_698d9b5380e40.png)

_698621d1aa8c4.png)

_698621ff95f59.png)

_6986222312669.png)

_698622539c8fb.png)